European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS): Interoperability as innovation?

The ESRS has been hailed as innovative, a watershed. We study its innovativeness relative to existing corporate sustainability policies and find that its not innovative in the language it uses. But that’s not a bad thing. It is a significant advance in terms of aligning with private sustainability reporting frameworks and standards. It should be celebrated for how it enshrines legal reporting requirements and how it advances the interoperability of sustainability standards.

This week marked a significant milestone as the European Commission formally adopted the much-anticipated European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). The ESRS have been hailed as a “game changer” and a “major milestone for robust corporate reporting”, representing nothing less than a significant policy innovation in the field of sustainability reporting. It is a policy that both strives to be a watershed and to augur for interoperability, for instance, with the GRI standards. So, just how innovative are the ESRS?

A policy can be deemed innovative based on the extent to which it deviates from similar policies already in existence. We can study the innovativeness of the ESRS by comparing it to other sustainability reporting frameworks and standards. We used the Carrots & Sticks (C&S) database, which is the world's most comprehensive ESG and sustainability policy dataset, constituting more than 2400 policies enacted by international organizations, regional organizations and national governments.

Leveraging the power of natural language processing (NLP), we measure the innovativeness of ESRS by analysing textual differences (or similarities) between it and policies in the C&S database. Specifically, we employ the widely-used cosine similarity metric, which quantifies the extent of text reuse between written documents. The cosine similarity result is a measure of policy innovativeness, ranging from 0 (indicating a lack of innovation) to 1 (denoting an exceptionally innovative policy)[1].

Same same but different?

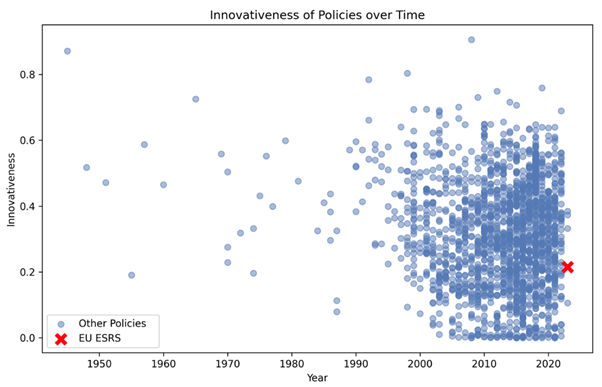

Figure 1 illustrates the “innovativeness” of all (English language) policies in the C&S database. The analysis reveals considerable variability in the degree of policy innovation across the dataset. For the ESRS, however, we find an innovativeness score that falls squarely in the middle of the spectrum, registering a score of 0.21. This score falls below the average policy innovativeness of 0.32, equivalent to approximately half a standard deviation. Consequently, our analysis indicates that the ESRS falls short of claims of innovation. Instead, it’s evident that the ESRS primarily draws upon and incorporates core ideas from pre-existing standards—and as such, seems to prioritize interoperability over distinctiveness.

Figure 1. How Innovative is the ESRS?

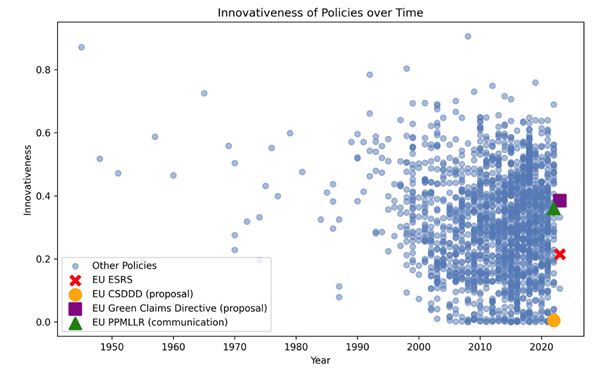

ESRS is not the only new corporate sustainability policy currently being considered by the EU. In recent months, the EU has introduced several significant initiatives. Notably, the proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) would mandate EU and non-EU companies to conduct due diligence on environmental and human rights impacts. The proposed Green Claims Directive aims to tackle greenwashing by imposing rules on accurate environmental marketing for EU and non-EU companies targeting European consumers. Furthermore, the Commission has published its Communication on the Prohibiting Products Made with Forced Labour on the Union Market Regulation (PPMFLR), seeking to ban products manufactured using forced labour.[2]

Does this deluge of sustainability policies bode for innovation or interoperability? Figure 2 provides initial insights into these proposals' policy innovativeness. The CSDDD exhibits minimal policy innovativeness, scoring even lower than ESRS. However, the proposed Green Claims Directive and the PPMLLR appear to offer more innovation, scoring higher than ESRS and well above the average policy innovativeness of 0.32. Of course, the text of these proposals will invariably undergo some change before being enshrined in EU law.

Figure 2. To what extent are other recent EU corporate sustainability proposals innovative?

The ESRS was clearly not forged in a policy vacuum. Rather, it draws liberally on existing policies—beyond the EU. Indeed, the design of the ESRS gives some clues regarding policy innovation, or lack therefore. For example, the ESRS is explicitly aligned with TCFD recommendations. At the same time, the ESRS draws upon existing standards, including the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). Equally, ESRS and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which recently issued its own new standards, managed to align on major concepts and requirements. This is particularly salient given that the new ISSB standards are “influenced” by TCFD, are “complemented” by GRI standards, and “consolidate” Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and Integrated Reporting (IR) standards and frameworks.[3] This all points to the prioritization of interoperability—and the pursuit of a shared, universal approach—rather than innovation.

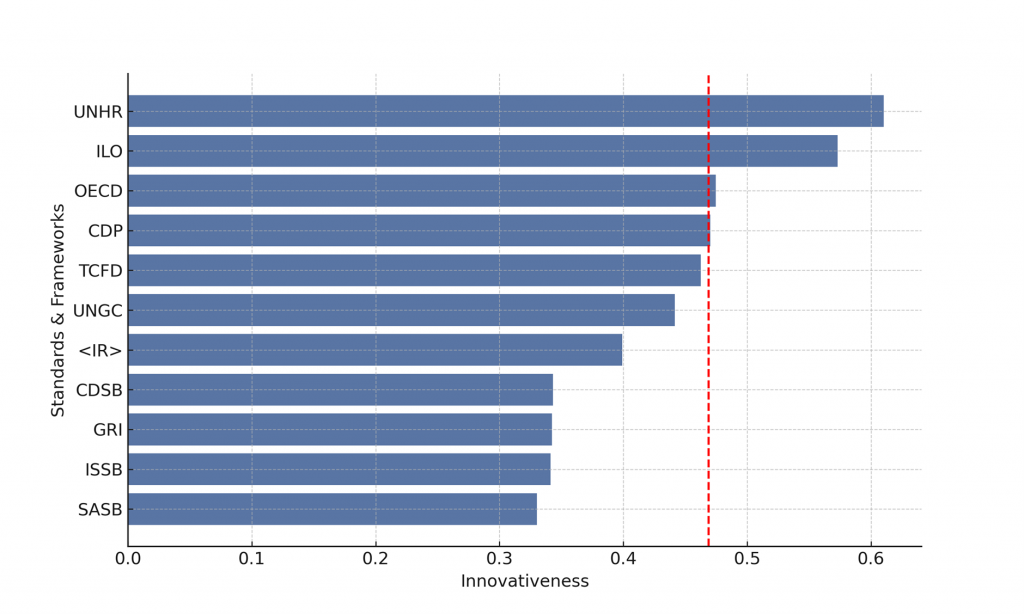

But what do the data say? Figure 3 shows just how much ESRS has innovated on these existing standards as well as those of several other major international standard setters including the International Labour Organization (ILO), OECD, the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), and the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHR). Our results show that the ESRS is the most distinct from the UNHR, ILO, and, to a lesser extent OECD. This is not surprising given differences in the scope and nature of these policies compared to ESRS. However, for the remaining standards, ESRS appears to be rather derivative, borrowing text most heavily from SASB, IFRS, GRI, and CDSB. Again, a positive reading of this is that the EU is aiming for interoperability with existing standards, including private initiatives.

Figure 3. How much does ESRS innovate on other key standards and frameworks?

Notes: the red dotted line indicates mean Policy Innovativeness (0.47) for ESRS policies compared to all other policies in the C&S database.

Convergence and legal requirement

The ESRS falls short of the anticipated ground-breaking change in sustainability reporting. However, it is vital to consider the real value of policy innovation in the broader context of addressing societal needs. Pursuing novelty for its own sake can lead to inefficiencies and unintended consequences. Interoperability—which manifests here as text reuse and incrementalism in introducing new text and ideas—offers a pragmatic approach that potentially engenders advances towards a shared global standard.

By building on existing frameworks, policymakers can leverage previous knowledge and refine approaches over time. They ensure standards align with the language and aims of those of other bodies, including private initiatives. While innovation brings potential for transformative change, responsible policy stewardship and convergence towards a universal standards. The ESRS may not be revolutionary, but it suggests interoperability as a motivating aim. It also, crucially, offers the “teeth” that private initiatives lack; EU standards can require disclosures in a way that voluntary standards cannot. In this sense, it is a watershed as the language and approaches that have proliferated from a number of standards and reporting bodies are now enshrined in EU law.

Adam William Chalmers is Senior Lecturer (European Union Politics) at the University of Edinburgh, School of Social and Political Science. His research, which has appeared widely in leading journals like Regulation & Governance, European Journal of Political Research, and Journal of Public Policy, focuses on corporate sustainability policy, corporate lobbying, and natural language processing. He is the academic co-lead of Carrots & Sticks.

Robyn Klingler-Vidra is Reader in Political Economy at King’s College London. She is the author of The Venture Capital State: The Silicon Valley Model in East Asia (Cornell University Press, 2018) and focuses on entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainability. Robyn is the second academic co-lead of Carrots & Sticks.

Photo by Nothing Ahead

[1] Joel Makower offers a good overview in “CSRD, CSDDD, ESRS, and more: A cheat sheet of EU sustainability regulations”.

[2] We borrow this approach from Pagliari & Wilf (2020) Regulatory novelty after financial crises: Evidence from international banking and securities standards: 1975-2016 Regulation & Governance 15(3): 933-951.

[3] For a good overview see https://www.kirkland.com/publications/kirkland-alert/2022/05/issb-proposed-framework