State of the World (According to The Economist)

Duncan Green on two excellent (gated) longer essays in last week’s Economist that explain the state of the world.

Duncan Green on two excellent (gated) longer essays in last week’s Economist that explain the state of the world.

The first was a graphic and alarming summary of the argument that ‘The world’s poorest countries have experienced a brutal decade’. Some extracts:

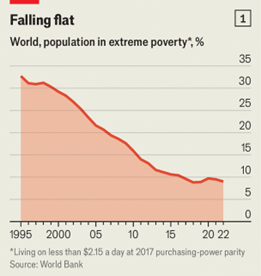

‘There are now a billion fewer people subsisting on less than $2.15 a day than in 2000. [But] almost all of the progress in the fight against poverty was achieved in the first 15 years of the 2000s (see chart 1). In 2022 just one-third as many people left extreme poverty as in 2013. Progress on infectious diseases, which thrive in the poorest countries, has slowed sharply. Developing-world childhood mortality plummeted from 79 to 42 deaths per 1,000 births between 2000 and 2016. Yet by 2022 the figure had dropped only a little more, to 37. The share of primary-school-aged children at school in low-income countries froze at 81% in 2015, having risen from 56% in 2000. Poverty is a thing of the past in much of Europe and South-East Asia; in much of Africa it looks more ingrained than it has in decades.

The poor world has, in short, experienced a brutal decade.

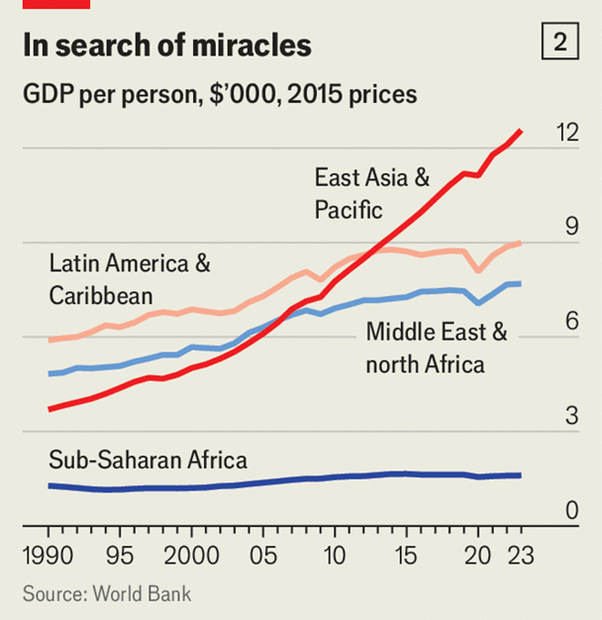

By the end of last year, GDP per person in Africa, the Middle East and South America was no closer to that in America than in 2015. Things are particularly grim in Africa (see chart 2). The average sub-Saharan’s inflation-adjusted income is only just above its level in 1970.

Aid is not coming to the rescue. In the early 2000s the unlikely duo of Bono, front man of U2, an Irish rock band, and President George W. Bush argued that the West had a moral responsibility to help the poor escape from poverty. There was no reason to wait for sluggish economic growth to do the job. By 2005 the world’s poorest 72 countries received funds equivalent to 40% of state spending from a combination of cheap loans, debt relief and grants.

Partly as a result, “external resources underpin much of the work of basic health systems from supply chains to drugs,” says Mark Suzman, chief executive of the Gates Foundation, a charity. By 2019 nearly half of clinics and two-thirds of schools in sub-Saharan Africa were built or had workers’ salaries paid by outside cash. The fight against malaria, tuberculosis and HIV, the world’s most deadly infectious diseases, is almost entirely reliant on such funding. Now, however, money is drying up as Western enthusiasm sags and new causes emerge. Today aid provides just 12% of the poorest countries’ state spending.

Competition for funding will only grow as climate change and rich-world refugee problems become more pressing. Last year, for instance, global aid flows on paper increased by 2%. Yet 18% of total bilateral aid was spent by rich countries caring for refugees on their own soil—a loophole that few countries took advantage of until 2014. A further 16% went on climate spending, up from 2% a decade ago. In total, the world’s 72 poorest countries attracted just 17% of bilateral aid, down from 40% a decade ago. At the same time, Chinese development finance has evaporated. In 2012 the country’s state banks doled out $30bn in infrastructure loans. By 2021 they handed out only $4bn.

Competition for funding will only grow as climate change and rich-world refugee problems become more pressing. Last year, for instance, global aid flows on paper increased by 2%. Yet 18% of total bilateral aid was spent by rich countries caring for refugees on their own soil—a loophole that few countries took advantage of until 2014. A further 16% went on climate spending, up from 2% a decade ago. In total, the world’s 72 poorest countries attracted just 17% of bilateral aid, down from 40% a decade ago. At the same time, Chinese development finance has evaporated. In 2012 the country’s state banks doled out $30bn in infrastructure loans. By 2021 they handed out only $4bn.

For their part, development economists are refining smaller and smaller interventions, rather than trying to come up with ideas that might change the world. New research divides into two strands. One produces elaborate theories to explain how capital and workers in the poor world ended up producing less than their rich-world counterparts. Another crunches the numbers to come up with effective micro-projects. Researchers in both groups insist their work is only relevant to the countries on which it focuses. “There are just not many big ideas left in development,” says Charles Kenny of the Centre for Global Development, a think-tank. “Everything is about the plumbing.”

Pretty depressing stuff. The second article is a curtain raiser for the UN General Assembly and paints a graphic picture of the shift to a multi-polar world due to the USA’s ‘weakening clout’, accelerated by the war in Gaza. I was struck by this summary of the orientation of the big players:

‘For all its swagger, Russia has yet to recover from repeated diplomatic snubs, such as losing its seats at the ICJ and bodies such as the Human Rights Council and UNESCO (the education, scientific and cultural body). That said, Russia has thrown its weight around on a growing number of issues. It has helped to push UN peacekeepers out of Mali; halted the supply of UN humanitarian aid to areas of Syria controlled by rebels; and blocked the work of a panel monitoring North Korea’s compliance with UN sanctions. Russia, it seems, does not mind being the spoiler. “We see instability as a risk, as something to fix,” says a Western diplomat. “The Russians see it as an opportunity, and something to exploit.”

China plays an altogether different game, often supporting Russia but at times co-operating with the West, for instance on how to regulate artificial intelligence (AI).

At the UN, China stands as a defender of state sovereignty against the intrusions of outsiders, for example, in the use of economic sanctions. It reinterprets human rights as the expectation of economic development, rather than individual liberties; and democracy as equality among states rather than the right of people to choose their leaders. It sees itself as the vanguard of the developing world, where it often finds a receptive audience for its interests-first, values-second approach. “Russia does not mind being seen as a wrecker of the system. China wants to remake it in its own image,” says a the diplomat.

As the big powers jostle, others seek space to manoeuvre. For instance, India pursues a “multi-aligned” foreign policy, triangulating between its old Russian friend and its newer Western pals. It has refused to impose sanctions on Russia, benefiting handsomely from the resulting trade. Turkey, though a member of NATO, has similarly stood apart from the West.

It is difficult to measure influence. Despite its troubles, “America is still the main game in town,” says a diplomat. But Western countries “are much easier to resist now than they were a few years ago”.

Yet many countries, especially those that feel threatened by bullying neighbours, are also drawing closer to America for protection. The war in Ukraine has fortified the NATO alliance. Similarly in Asia, where Japan, Australia and the Philippines have bound themselves more tightly to America, and to each other, fearing China’s military build-up.

In the Middle East mighty Israel has relied heavily on the presence of America’s armed forces to deter a regional war with Iran and its “axis of resistance”, and to help shoot down missiles fired at it. Gulf monarchies, which dislike Hamas, still seek American protection against Iran and several maintain ties with Israel. As for Gaza, only America has any chance of negotiating an end to the war.

Hobbled hegemon

America has belatedly woken up to competition with China for support in the global south amid signs that sentiment is shifting. An opinion survey of 31 countries found strong support for Ukraine in many of them. But respondents in India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt and Saudi Arabia sided more with Russia. The survey also found strong support for American leadership in the world, though places like Turkey, Egypt and Saudi Arabia leaned towards China.

A separate annual survey of elite opinion in South-East Asia for the first time recorded a majority saying that if asked to choose between America and China, they would side with China in a crisis. Western diplomats say it has become harder to meet senior figures in Muslim-majority countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia. Some in America’s Congress worry the damage to America’s standing is becoming irreparable, though they also think showing loyalty to an embattled ally will reassure friends worldwide.’

This first appeared on From Poverty to Power.

Photo by Pixabay