Is Social Democracy facing Extinction in Europe?

One of the more surprising aspects of Labour’s strong performance in the UK’s general election is that it came at a time when social democratic parties have experienced falling support in other countries across Europe. Davide Vittori asks whether the exceptionally poor results of parties such as the French Socialist Party in recent elections heralds the end of social democracy as we know it in Europe.

The last French presidential election and the recent legislative elections confirmed a seemingly unstoppable declining trend in the electoral support of social democratic parties. For the second time in the last fifteen years, the official candidate of the French Socialist Party (PS) was excluded from the second round; in both cases, the “outsider” was represented by the candidate of the Front National (FN).

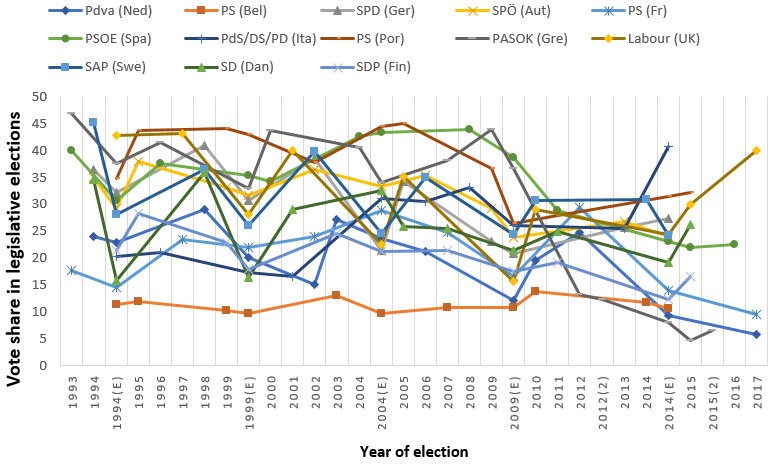

The legislative election confirmed this trend: the PS and its allies received only 9.5% of the vote. Before the French elections, the Labour Party (PvdA) in the Netherlands (5.7%) received a similarly cataclysmic result. This built on other high profile losses for social democratic parties in recent years, notably PASOK’s decline in Greece in 2012 (13.2%), which represented a turning point for the Greek political system. Between these results, other social democratic parties have suffered heavy losses, either as incumbents or as parties in opposition. Figure 1 below shows how the electoral picture has changed for thirteen social democratic parties in western Europe since the early 1990s.

Figure 1: Electoral performance by selected social democratic parties in western Europe since 1993

Note: Figures compiled by the author up to the UK general election on 8 June 2017.

The one clear exception in recent elections was the surprise result achieved by Labour in the UK’s general election on 8 June. But despite this result, the overall picture is one of declining support for social democrats. All this considered, what lies behind this decline and is it irreversible?

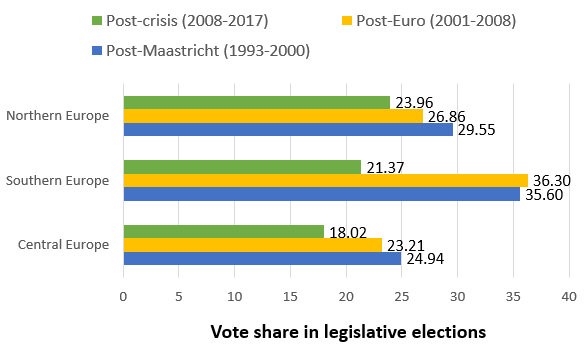

Although academic literature often emphasises the importance of electoral laws in modelling party competition, the social democratic decline encompasses all types of electoral laws (from proportional to majoritarian laws). What emerges from a very brief longitudinal analysis of the social democratic share of votes in thirteen western European countries is that the 2007-09 economic and financial shock represented a turning point. Although average vote share may not be the best indicator in this case, the results in three western European macro areas – northern Europe (UK, Sweden, Denmark, Finland), southern Europe (Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece) and central Europe (France, The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Austria) – are telling.

In particular, when dividing the post-Cold War situation into three periods – the post-Maastricht period (1993-2000), the post-euro period (2001-2008) and the post-crisis period (2009-2017) – social democratic electoral decline is evident especially in the last period. In the northern and central countries, the decline was steady but irreversible: here, social democratic parties represent less than 1 out of 5 voters and the scenarios depicted by the polls for the other elections – Germany (September), Austria (October) and Belgium (2019) – is rather problematic.

Figure 2: Performance by social democratic parties in three regional groups

Note: Figures compiled by the author up to the UK general election on 8 June 2017.

In southern Europe, the social democratic decline was more marked than the other two areas. The interest rate bonanza and economic growth which followed the introduction of the euro benefited all social democratic parties. The “reformist” era – marked by a strong Europeanism coupled with a pro-market stance – resembled in some ways the success of the Third Way inaugurated by Tony Blair in the United Kingdom. Costas Simitis in Greece, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero in Spain, and José Sócrates in Portugal represented the new faces of this successful social democracy. In Italy, the culmination of the transformation of the centre-left was the merging of the left-Christian Democrats and the Left Democrats (the successor of the Italian Communist Party) into one “reformist” party, the Democratic Party (PD).

The average share of votes for the southern European social democratic parties between 2001 and 2009 was 36.3%. By then, these parties had lost almost fifteen per cent of their voters. The PASOK case became a paradigm for the social democratic collapse: indeed, the phenomenon is sometimes referred to as ‘pasokification’. A similar fate, albeit far less dramatic, affected the Spanish PSOE, whose pre-eminence in the centre-left field has recently been challenged by Podemos, and whose leadership was removed via an ‘internal coup’ at the end of 2016. Even the ‘counter-cyclical’ case of the Portuguese Socialist Party, which recently formed a coalition government with the Left Bloc and the Portuguese Communist Party, involves a party that has been far less successful in the post-crisis period than it was in the past. Finally, Italy’s PD, having initially received strong backing under the leadership of Matteo Renzi, suffered a significant defeat in a constitutional referendum in December.

The countless analyses that have been conducted on the growth of so-called anti-establishment parties in Europe – both coming from the radical-right and radical-left –highlight the impact of new parties in post-crisis political systems. This impact is felt in terms of electoral relevancy, agenda-setting and, when in government, policy-making. The new wave of anti-establishment sentiments – though not entirely ‘new’ from a political-science standpoint – will also have an influence on mainstream parties, both from the right and from the left. This is particularly true because many anti-establishment parties instinctively reject the concepts of ‘left’ and ‘right’ when making their appeals to voters. They emphasise the growing importance of post-materialist issues, which cut across the left-right economic dimension, and the alleged ‘cartelisation’ of mainstream parties.

According to the theory of cartelisation, cartel parties are state agents, which rely almost exclusively on public funding for their activities; thus, they tend to relegate members to a cheerleading role, preferring collusion rather than competition with other ‘cartelised’ parties. More importantly, cartel parties tend to prefer responsibility to supranational institutions over responsiveness to the electorate. This image of a cartel party is the exact opposite of the mass party organisation which is typically associated with ‘old’ social democratic parties, who were assumed to have a higher level of responsiveness to the electorate, and a wide membership which was the source of much of the party’s funding.

Whether the theory of cartelisation is taken at face value or not, there has clearly been an organisational transformation in most social democratic parties over recent decades. Many have effectively become ‘catch all’ parties, though there are differences in how this has taken place in accordance with the national contexts in which parties operate. Social democratic parties have also exhibited strong support for European level policies. The trade-off between responsiveness to national electorates and support for EU-level agreements was perhaps hidden prior to the financial crisis, but in the post-crisis period, this distinction has become far more visible. Many social democratic parties, particularly those in government, became responsible (or partly responsible) for implementing restrictive EU policies following the crisis, notably in France, Spain, the Netherlands, Greece, and Germany.

Whether these shifts in support are permanent remains to be seen. What is clear is that at present many social democratic parties are both organisationally and ideologically ill-equipped to provide concrete answers for an increasingly dissatisfied electorate. And if this trend continues, we may well be witnessing the end of social democracy (as we know it) in Europe.

Davide Vittori is a PhD candidate at LUISS University. His main research interests focus on party politics, movement parties, party organisation and populism. His last article on the Italian Political Science Review deals with the cartelization within social-democratic parties. This post first appeared on the LSE's EUROPP blog.

Photo credit: chrisjohnbeckett via Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND