Reaching Across Cultural and Political Divides: Why Dialogues Matter and How They Can Succeed

Joel Sadhu reflects on 10+ years of experience and lessons learned from GPPi’s dialogue activities, focusing on Global Governance Futures – Robert Bosch Foundation Multilateral Dialogues.

In December 2020, United Nations Secretary General António Guterres addressed the German parliament with a warning: he voiced his concern about the growing distrust between states as well as the lack of international cooperation on key issues, such as climate change. Bemoaning the rise of nationalist, isolationist and populist sentiments around the world, he was worried that “in too many places, we see a closing of minds.” Guterres also reiterated the need for global solutions to global challenges: “It is clear that the way to win the future is through an openness to the world.” In other words: to end and reverse the current spiral of distrust, we need more engagement and open dialogues between countries, between the people who are politically divided within them, and between people with diverse backgrounds.

The Global Governance Futures (GGF) Multilateral Dialogues fellowship program, which ran from 2010 to 2021, offered one such platform to young professionals who are eager to play an active role in thinking about and shaping tomorrow. The program aimed to create space for and facilitate meaningful dialogue between the fellows – through active listening, structured reflection on fellows’ assumptions and preconceived notions about the world, through constructive communication and negotiation as well as solution-oriented discussions about global problems that cannot be solved by any one individual, organization, society, or state alone. The basic premise of the program: such issues can only be tackled if individuals come together and work across divides. Efforts to address them can only succeed if people listen and talk to each other, jointly explore and aim to understand their differences, work collaboratively, reach consensus where possible, jointly make decisions, and act collectively in the interest of the global community. It is in this spirit of collective learning and with the objective to find better ways to address transboundary challenges that the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) launched the GGF fellowship in 2010, with generous support from the Robert Bosch Foundation and the Transatlantic Program of the German Federal Government. [1]

But how do we meaningfully engage with worldviews that we disagree with? How can we address the geopolitical tensions arising between countries to strengthen our collective ability to jointly tackle global challenges? What does it take to facilitate dialogues that bring about constructive change – rather than frustrating miscommunication? And how can we bring a wide range of voices to the table and develop potential solutions to global challenges that work globally and locally? Our experiences and learnings from over ten years of facilitating international dialogues have allowed us to answer at least some of these questions. In this article, we lay out why we think more of these efforts are needed, how we can make cross-cultural policy dialogues work, and which outcomes we can – and cannot – expect from them.*

Why Dialogue Matters

Besieged by forces such as right-wing populism and a global renaissance of authoritarianism, democracies around the world are under assault. Suspicion and mistrust are surging both within and between countries. Communication and cooperation between governments are dwindling while accusations and defensiveness flourish, even – and in some instances, especially – in the face of a global pandemic that does not discriminate and has spared no one. Geopolitically, the global centers of economic and political power have shifted over the last two decades – from the West (led by the United States) to the East, particularly Asia (led by China). At the same time, we have been witnessing the rise of influential movements demanding bolder action on global issues, first and foremost on climate change. How can multilateral policy dialogues help address and constructively channel these forces?

If done mindfully, multilateral policy dialogues are an opportunity to deepen our knowledge by leveraging the intelligence of both our head and heart. We need dialogues because without them we drift apart. Our differences – be it at the local, national or international level – become misleading and our fears of ‘the other’ intensify. “It is dialogue that allows non-violence to work, that links and binds us. (…) It is dialogue that invites us to understand and open our hearts to each other; it is dialogue that expands and sustains our capacity for love and connection,” writes Ken Cloke, an experienced international facilitator in the field of conflict resolution. Dialogues are also an opportunity for us to reflect on our mental models as well as our biases and judgments, and to expand our thinking. As Philip E. Tetlock observed, “[m]any judgmental shortcomings can be traced to a deeply ingrained feature of human nature: our tendency to apply more stringent standards to evidence that challenges our prejudices than to evidence that reinforces those prejudices.”[2] Building on these insights, the GGF program exposed the fellows to different local, national and professional perspectives, both with regard to the policy issues they focused on and concerning broader discussions on global governance. It allowed them to reflect on their biases and to challenge their mental models.

Critics of multilateral dialogues (and multilateralism, for that matter) often formulate fierce doubts about the effectiveness and capacity of multilateral forums and institutions like the UN, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to deal with recurrent and protracted crises – be they economic, political, ecological, or humanitarian. They question the usefulness of engaging other parties as opposed to “going it alone.” But even for those who believe that efforts to build consensus and trust within multilateral dialogues are pointless, or who subscribe to a realpolitik view of what happens in multilateral meetings and negotiations, multilateral dialogues can serve as a valuable tool. They allow us to know how people ‘on the other side’ think and to understand the concerns, interests and priorities that drive them. Dialogues can either challenge or reaffirm our convictions. At the very least, through this added insight, they offer us a chance to avoid falling into traps of misperception, thereby helping us to make better judgments.

GGF fellow Shireen Santosham speaking at the opening session of GGF 2027, which was hosted at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC.

“Does it not cost more to continue conflicts that were triggered by failures of communication and collaboration than to invest the time, effort and skills that are needed to overcome hurdles to cooperation?” asked one of our GGF 2022 alumna in 2012 during her cohort’s dialogue session in Berlin. In line with this sentiment, the idea of learning from one another was one of the cornerstones of the GGF multilateral dialogues. Our aim in designing the fellowship was to establish an effective platform that would allow young policy professionals from different world regions and walks of life (who otherwise would not have met) to come together, get to know each other, and understand and learn from each other through a series of facilitated dialogues. In six rounds of the program, the 152 GGF fellows engaged in discussions that allowed them to jointly explore the normative convergences and divergences between and within their home countries. One alumnus from the United States, who now works in the Biden-Harris administration, once shared that he learned through GGF that fellows from other countries saw the challenges the cohort had been discussing in a way that starkly differed from how these topics were debated in the US. In a feedback session, he remarked that the “GGF experience left me smarter than before I came in.” Expressing a similar sentiment, a number of fellows have stated over the years that the insights they gained through the program enriched their understanding of both the global challenges that were the focus topics of their cohort and other countries’ perspectives on them. The GGF dialogues consequently prepared the fellows to engage in national debates and discussions with informed arguments and a broadened understanding of the issues at hand.

We approached the design of the GGF program with a clear and realistic view of both the challenges and the opportunities that multilateral dialogues present. We were careful to craft a method that would enable the fellows to challenge each other’s ideas, reflect on their own assumptions and jointly explore concrete policy options and interventions in the face of an uncertain future. The debates and discussions that resulted from this were captured by the fellows in a series of reports that reflected their shared understanding, while simultaneously highlighting the divergences that their countries must overcome to jointly confront pressing global challenges. [3]

GGF fellows Helidah ‘Didi’ Ogude (L), Astha Kapoor (C) and Angela Pilath (R) presenting their working group’s scenario report at the Robert Bosch Foundation Berlin Representative Office.

Our Approach

The greatest asset of the program was the diversity of our fellows: three each from nine countries that represented different parts of the world – East and West, Global South and Global North – as well as the public, private and non-profit sectors. During a series of dialogue sessions spread out over the course of one year – with each meeting taking place in a different country and lasting several days – the different GGF cohorts all developed a collective energy that allowed them to foster a deep sense of community. Through genuine and repeated efforts to communicate with each other, they emerged from these sessions with a better understanding of and trust in each other.

The working process for each round of the program drew on the GGF method (see also, Set a Framework with a Common Goal and Use Generative Formats below) to combine the unique strengths, experiences and perspectives of each fellow as the group worked toward a common goal. Because of that, we succeeded in creating relationships that lasted beyond the duration of the fellowship and live on through an active alumni community. Over the past ten years, we convened six GGF cohorts, resulting in a network of over 150 program alumni. Today, the former fellows from the first cohort have an average of 10 to 15 years of professional experience, some even more. Over the years, the GGF fellows’ professional backgrounds included academia, the private sector, government and public service, the arts, the non-profit sector, journalism, medical and engineering professions, and more. This diversity always made their discussions an insightful and multidimensional experience.

The program also thrived because of the support and commitment of a diverse set of partner institutions from the GGF participating countries. Our network of partners consisted of leading academic institutions, foundations and think tanks. [4] These organizations hosted the GGF sessions in their respective countries and supported with outreach, among other things. They also brought in national leaders from diverse sectors as well as their own experts and researchers, who engaged with and debated the fellows on global policy issues during the sessions.

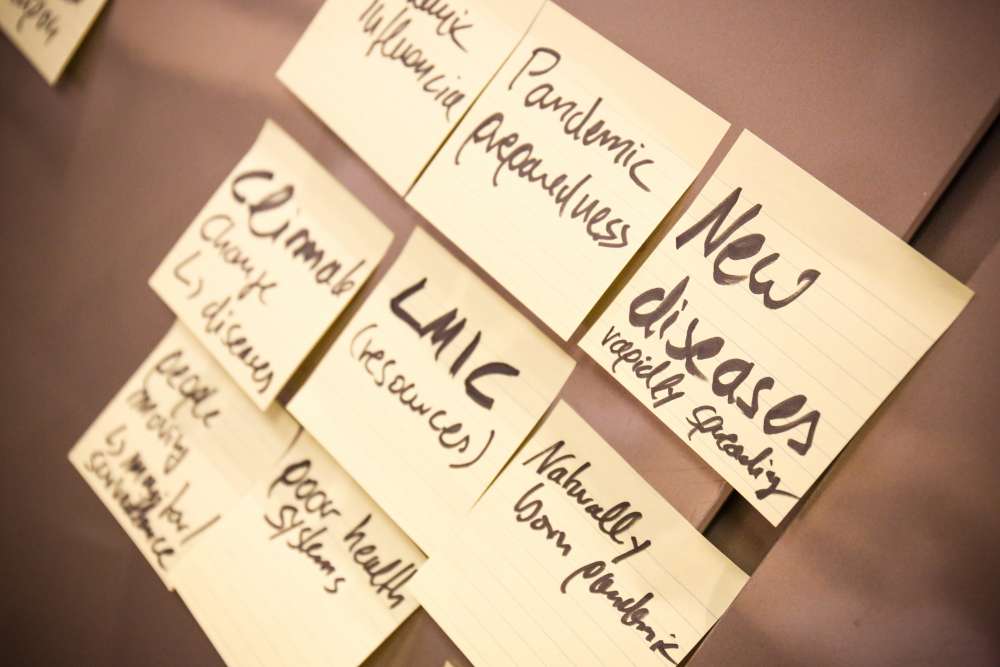

Over the last ten years, we covered a broad variety of pressing global governance issues – ranging from nuclear security, economic governance, cyber security, and global development to geoengineering, the future of the global order, and global health and pandemics to transnational terrorism, the role of cities in global governance, refugees and migration, climate change, and the future of the global media and information landscape. Each GGF cohort (divided into three sub-groups) spent a year exploring three focus topics and was tasked with developing ways to better address these global challenges. To help them in this endeavor, the GGF method – which combines scenario planning and generative facilitation – provided an intellectually challenging framework that enabled structured communication and rigorous thinking about different futures and ways to shape policy outcomes. The fellows used the GGF method to construct plausible future trajectories for their working group’s topic and thus arrived at a better – and shared – understanding of the challenges that lie ahead. At the same time, it helped them identify the key divergences that their respective countries and professional sectors must overcome to jointly tackle pressing global challenges.

During their time together, the fellows not only engaged with each other but also met experts, policymakers and other thought leaders who tested and discussed their findings with them. In doing so, the fellows explored policy options that take into account both political realities and uncertainties. On an individual level, the fellows were encouraged to turn the knowledge they gathered into concrete recommendations for decision- and policymakers, both in their home countries and international organizations. Their analyses and suggestions are available to the public and can be accessed through the GGF website.

GGF 2027 fellows reflecting on their group work during the final session in June 2017.

Essential Ingredients for Meaningful Dialogues

The number one prerequisite for open and constructive dialogue is trust. Because of that, we focused on developing working and personal relationships between young professionals from countries that are not only competitors on the global stage, but are also vastly different in terms of language, culture, political systems, and economic development. We designed, developed and, after each round, updated a structured approach to communication that allowed our fellows to identify and address the competing views that global governance fora will have to manage in order to address key global issues. Based on our experience with this approach, we identified five different ingredients for successful multilateral dialogues.

Set a Framework with a Common Goal

How does one provide a structure that allows individuals to be open to multiple perspectives while also shepherding a highly diverse group toward a common goal? We developed a structured communication framework that combines instruments from the discipline of strategic foresight, including scenario planning and risk assessments, with generative facilitation techniques that moved the group from a problem-oriented to a solution-oriented mindset and ultimately steered them toward a collective outcome.

The scenario planning and group facilitation methods ensured that all voices in the working groups were heard and had equal weight. We chose to employ scenario planning because we believe that, when it comes to the future, no one can claim a monopoly on the truth. Our approach allowed all the fellows an equal say in exploring and formulating how their working group’s topic might develop in the next 10 to 15 years. Because scenario planning requires multidimensional thinking, the GGF method made it easier for our fellows to work across both cultural divides and sectoral boundaries. Importantly, the exercise was not about predicting the future, but about jointly imagining possible futures that will affect us all but will also inevitably surprise us. Together, the fellows developed, shared and refined their assumptions about the future and thought of ways to promote the most desirable outcomes while preventing or mitigating the least desirable scenarios. Ultimately, the GGF approach allowed us to have creative and insightful conversations across political and cultural divides.

Another common goal for all of the working groups was to co-create a final scenario report that was published at the end of each GGF round. This pushed the fellows to actively listen, engage in teamwork, jointly solve problems, share constructive feedback, and collaborate on a joint project, all while dealing with and – in the best cases – appreciating their differences. By asking the right questions, the working group facilitators steered the debates from hypothetical and vague toward joint discovery and deeper conversations that catalyzed learning. As a result, the program facilitators helped the fellows develop precise scenarios and spell out concrete policy implications and recommendations for different target audiences. The scenario reports thus reflected the fellows’ shared efforts – and they were proud to see their names featured in the bylines.

GGF 2027 global health working group brainstorming about the future of public health in 2016.

Invest in Building Trust Across Boundaries

The time and attention that the GGF fellows invested in the program were key to developing mutual trust. Each cohort met at least three times in different cities, and each meeting lasted five or six days (adding up to about 24 days in one year). This allowed the program team to create a diverse agenda and include different formats of interaction that went further than mere content discussions. These included activities like dialogue walks in pairs and trios, joint cultural activities in the respective city, visits to local social projects, informal discussions on the sidelines of the official program, and cooking or sharing food together. This shared time created the necessary space for the fellows to meet each other as individuals independent of national or sectoral backgrounds, and to connect beyond their respective professional roles. As GGF fellows, they were more than a representative from a certain field or country – they participated as a multifaceted person, thus discovering commonalities with other fellows despite the different national or professional socializations. The time they invested in getting to know each other during and outside the official meetings laid the foundation for the trust that allowed for deep and sometimes difficult discussions, including about highly sensitive or charged political subjects.

It takes time and a strong commitment by all participants to have such deep and at times intense exchanges. But all the fellows saw this experience as a unique opportunity. As one alumnus from the first cohort described it: “Taking off from work and all the [private life] things you need to do, to focus on one thing, in one place, allows us to think deeply about one subject in a way that becomes very rare in our lives.” By investing in the development of trusting relationships and a shared commitment to the process, we were able to help our fellows address issues more deeply and to unlock their imaginations to see and understand a wider set of potential solutions.

GGF 2030 fellows Aidy Halimanjaya and Max Bouchet listening deeply during a discussion in Paris in May 2019.

Employ Generative Formats

A famous quote often attributed to Albert Einstein says that “[w]e cannot solve problems with the same kind of thinking that created them.” This holds true for many global governance challenges. However, the modus operandi in world politics still tends to be reactive problem-solving. More often than not, we and our political leaders are stuck in – and thus reinforce – certain patterns of thought or behavior, instead of developing (or generating) new visions for and mental models about the future.

The idea of generative group formats is to create a future instead of merely reacting to current problems. The goal is to move beyond reaction and fragmented problem-solving toward a more forward looking approach that promotes good governance. Over the years, generative formats have allowed the GGF fellows to share their human experiences and to see the world and different realities from perspectives that differ from their own. Such formats tap into both the open mind (cognition) and the open heart (empathic listening) in order to activate a “capacity to connect to the highest future possibility”[5] – a forward-looking vision. As such, the role of the GGF facilitators was to draw out the groups’ shared creativity and thus foster “innovation to our systems and navigate journeys of collective discovery around what our best future might look like.”

One such generative exercise we practiced with the most recent – and last – cohort of fellows (GGF 2035) was a format called “Future Search”. In a nutshell, Future Search is an exercise that allows a group of participants to create a shared vision of its possible futures. The format encourages commitment from all stakeholders and helps generate energy for action. In a cross-cultural Future Search, like the one we tested with the GGF 2035 fellows, the different steps included drawing individual timelines, mind maps and preferred future scenarios before working collectively on how to get there through prototyping. As Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff noted in their book Future Search, “the processes provide a neutral bridge that diverse people could walk to find one another.”[6] Because the labels of “past, present and future” belong to no one culture, the fellows used their Future Search exercise to “recreate their own cultural contexts, projecting onto a blank page (…) what they valued most.”[7]

Reflecting on this process, one GGF 2035 fellow remarked: “If you remove the emotions from the conversation, you never get the full perspective.” Because emotions are always part of the picture, whether consciously or not, this facilitation approach helps create “environments to bring out emotional perspectives in addition to rational arguments and debates.”

GGF 2035 fellows engaging in a Future Search workshop in Brač, Croatia in September 2021.

Ensure Professional Facilitation

The presence of professional facilitators who are trained in generative formats is an important factor in successful dialogue processes. That holds especially true for multilateral and multi-stakeholder dialogues. In addition to a well-trained facilitation team, a successful dialogue program requires plenty of preparatory work. For GGF, this involved a consciously designed and implemented selection process to guarantee a mix of participants who were passionate about the GGF focus topics and open to learning and being challenged, who were aware of their own biases and limitations, and who demonstrated a desire to grow and connect with people from other parts of the world.

For such highly diverse groups, communication, negotiation and joint problem-solving require the right setting. That means paying attention to ensure that facilitators employ the appropriate discussion formats and use techniques that engage participants in generative dialogues. It also means moving from problem- to solution-oriented discussions that combine the different perspectives in the room. The intention is to help the group become more effective in bringing forward new ideas and in contributing to constructive transformation in their policy fields. Raymond Cohen, a professor of international relations at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, believes that there is a growing need for professional facilitators and mediators to consider and emphasize “prenegotiation” (or pre-meetings), especially for multilateral dialogues and negotiations. [8] This includes identifying potential points of conflict, mapping normative convergences and divergences, and engaging in problem-solving exercises and other possible ways to overcome deadlock.

Additionally, for a smooth execution of the program, we:

- Prioritized detailed event management so that the program ran smoothly, people felt safe and secure, and were therefore more likely to relax and open up;

- Invited external experts, speakers and guests who could help the fellows identify blind spots in the groups’ discussions and who shared the space with the fellows instead of taking center stage;

- Selected the best possible locations for different informal interactions (e.g., breakfast, lunch and dinner venues, hotels, etc.);

- Remained mindful about the power of place to help us connect the external and with our internal worlds and thus invested in finding ideal locations for formal group interactions to encourage meaningful dialogues;

- Ensured the right balance of activities on each day and throughout the week (which meant carefully selecting interactional settings, alternating the pace of different activities, finding different ways to activate the head, heart and hand, etc.).

GGF 2030 fellows Jodi Allemeier (L), Ryo Ishida (C) and Carolina Guimarães (R) working on a scenario timeline.

Co-Sensing the World Around Us

During each round of the program, our GGF fellows travelled to several of the participating countries, who each hosted dialogue sessions. (A notable exception was the last round of the program, which took place during the global COVID-19 pandemic.) In each country, the groups travelled together to explore the respective cultures and societies. They shared meals and drinks, engaged in conversations with locals, visited the homes of other fellows or alumni who lived in the host city, and discovered new things. Together, they immersed themselves in the cultural and political fabric around them by using all of their senses: sight, sound, taste, and touch. They did not just talk and think together – they also experienced and felt together, and they had fun.

Engaging with locals allowed the fellows to break “out of elitist conversations and circles,” as one alumnus reflected. We thus consciously involved the perspectives of people who are not experts or policymakers but wished to change the status quo and improve their own well-being as well as that of their communities, for instance by engaging with local high school students. These conversations presented opportunities to bring up issues that were not necessarily at the center of attention in every policy circle (such as so-called identity politics) but the trajectory of which rested on political decisions in some way. By allowing the fellows to co-sense different cultures and places, we created “situational experiences” in which they immersed themselves in the environments about which they were having (often rather abstract) discussions. By witnessing and experiencing different local realities and struggles, such as a lack of access to vital resources, and by recognizing people in their broader humanity, our fellows made lasting memories that helped – and will continue to help – them understand the everyday, practical consequences of policy choices in different communities around the world.

Overall, the co-sensing experience allowed the fellows to shift their perspective – sometimes fundamentally so – and to activate and leverage “the intelligence of the head, heart and hands by nurturing curiosity, compassion and courage” when discussing global governance challenges in different geographies. As Otto Scharmer and Katrin Käufer observed, co-sensing experiences allow participants to move from an ego-system to an eco-system awareness: “Decision-makers across the institutions of a system have to go on a joint journey from seeing only their viewpoint to experiencing the system from the perspective of the other player[s].”[9] As a result, the GGF fellows developed a deeper ‘sense’ of the topics and issues they were thinking and talking about.

Based on these observations about ‘what works’, the following sections looks at the lasting impacts the GGF program has had on our fellows. It is based on a series of interviews we conducted with selected GGF fellows and alumni during July 2021.

GGF 2020 fellow Bruce Au socializing at the Alumni Reunion in June 2017.

Lasting Impacts

Looking back at a decade of designing, facilitating and carrying out multilateral dialogues with over 150 GGF fellows from all walks of life and backgrounds, we are humbled by the lasting impact of our ambitious endeavor. Our hope was always that the fellows and alumni would carry their experiences and insights beyond the program and into their decision-making as future leaders in their respective countries, organizations, communities, and professions. The subsections below sum up what they found to be the most valuable aspects of the GGF program.

No Room for Echo Chambers

Their experiences as participants in the GGF multilateral dialogues allowed our fellows and alumni to get out of insular (national) policy debates. One alumnus, who currently works in the German public service noted that he became more aware of his own narrow paradigms: “In many organizations and institutionalized settings, group thinking occurs. It is very helpful and important to hear from others – also to realize that your own paradigms are not as obvious as they might seem from within your group.” The fellows also became aware of their own biases and recognized the limitations of their thinking. With regard to discussions about different approaches to local and global policymaking, one alumna from the US noted that “differences in tactics or strategies do not always mean differences in values.”

Many also remembered uncomfortable conversations during their GGF experience as positive catalysts for learning. As one alumnus from the first cohort put it: “Being okay with disagreeing, letting the disagreements sink in, and then reengaging in a meaningful exchange without getting defensive and defending your organization’s point of view was a refreshing experience.” Another alumna fondly recalled feeling challenged by her cohort: “It is very valuable to work and talk with people who do not tell you what you want to hear. That happens all too often in the sector I work in.”

Expanding Networks and Deep Relationships

Through GGF, we helped promote personal and professional relationships that lasted beyond the respective program cycles. We organized regular GGF alumni reunions to develop a sense of community by jointly shaping and implementing these events with our fellows and alumni. This has given them a feeling of co-ownership not just within their cohort but in the entire GGF program. Subsequently, our alumni frequently self-organize and continue to hold regular local meet-ups. Many also welcome and host other GGF alumni when they visit their home town. GGF alumni also played an active role in our preparations for as well as during each round of the program: they nominated promising candidates during the application process, participated in GGF dialogue sessions as speakers for the entire cohort or as experts in the working groups, and opened their homes to host social evenings. An alumna from South Africa highlighted the importance of close relationships for the policy world, saying that “some of the biggest political shifts you have is through intimate relationships; intimacy is political.” The relationships that emerged during each fellowship round continue to be valuable even years later. Reflecting on the friendships she built during her time as a fellow, one alumna from the second cohort said: “I continue to tap into the GGF relationships. I came out with a network of people that I can call up and ask ‘stupid’ or ‘out-of-the-box’ questions that I would usually not ask a professional colleague.”

One such concrete example of a cross-cohort cooperation happened in Washington, DC in 2018 when a US-based alumnus organized a fundraiser to support the Michigan gubernatorial election campaign of another alumnus from a later cohort. The organizer invited people from his personal and professional networks, including locally based fellows and alumni, to attend the event. Both alumni attributed this support across GGF cohorts to the fact that the GGF alumni were part of a wider community that shared a similar experience and journey, perhaps even comradery. The event and show of support were a reflection of deep connections. As the organizing alumnus put it, “I want to see us succeed in what we do.”

GGF 2027 fellows applauding the winning team of a scenario game.

Another example of post-GGF cooperation occurred after the final round, GGF 2035, when two US fellows explored opportunities to use and replicate some of the instruments they learned during the program and apply them to foster youth dialogues in their home country. The intention behind their idea is to help young Americans better understand each other. The collaboration between the fellows is the direct result of new networks created during the program as well as our approach, which emphasizes deepening trust among people and giving them transferrable skills that they can apply to their own passions and work.

Still, a number of fellows also said that they wished they could have spent even more time getting to know each other, especially in cases where they did not get to speak with everyone in their cohort. If we had the opportunity to do things differently, we could imagine spending more time on those formats that allowed the fellows to engage with each other as individuals, not just as issue experts. Storytelling, for example, is a fantastic method to practice active listening – that is, mindfully paying attention to what is said and staying connected to the spoken word without judgement, criticism or blame. Storytelling renders abstract issues more accessible and allows for connection and emotional resonance between people. Program participants could talk about how a given global governance challenge has impacted them personally, and share insights into their lived experience and how this has shaped the person they are today. Across cultures and communities, storytelling has served as one of the strongest practices for humans to bond over. Listening to each other’s stories builds empathy, forges trust and creates deeper connections. It is a highly effective way to leverage emotions with meaning and intention. As one fellow from Brazil pointed out: “Every time you learn new content knowledge, in 30 years that knowledge is going to be outdated. Every time you get to know someone – and really get to know them in a purposeful way, in an intentional way, around an issue – in 30 years, that network is just going to get stronger and stronger and will continue to feed your knowledge.”

Over a decade of organizing the GGF fellowship program, we learned that the networks and relationships our fellows build help them update their knowledge over time. And in hindsight, we could have created even more space for such interactions that expand networks and deepen relations. [10]

GGF 2030 fellows bursting out laughing during a photo presentation.

Personal Growth and Skill Development

“GGF has opened up my world; it has been a transformative experience,” recalled one alumnus during his interview. And indeed, during their time together the GGF fellows frequently challenged each other’s mental models and convictions. As a result of that, an overwhelming majority of them claimed that their intellectual horizons had expanded through the program. [11] For many of them, the program involved a steep learning curve that led to personal growth and helped them acquire concrete transferable skills, first and foremost the methods and instruments of strategic foresight. As one recent fellow commented: “Leaning scenario planning and the different communications methods that Joel and the team taught us was really useful. I intend to use them within my organization in Indonesia.”

One alumna from India recalled how she benefited from learning the GGF foresight methodology: “This skill set was ultimately the reason I got to work at the United Nations, which really valued these capacities.” Overall, a number of GGF fellows transferred aspects of the GGF method to their professional work. As one former participant put it: “GGF was not just about the report as a product. It was learning about the process – also for applying it elsewhere under different circumstances.”

By engaging with a diverse set of perspectives, the participants often experienced first-hand that there is usually more than one ‘reality’ or ‘truth’. In the words of Ken Cloke: dialogue is about accepting “different, co-existing, ‘alternative’ truths, each representing unique personal and group experiences, all of which can be regarded as valid from the narrow point of view of the person or group that experiences it.” Even if their points of view at times seemed to contradict one another, the participants learned that all can be true at the same time. In these interconnected and complex times, the ability to tolerate, navigate and even embrace this ambiguity is a core leadership skill.

New Opportunities

The GGF program has served as a “launching pad” for international networks as well as local policy circles in the alumni’s home countries and cities. Several alumni spoke of how their participation in the fellowship program had opened up new professional opportunities for them. As one alumna described it: “The program opened up different collaboration opportunities for me (…). I visited [a GGF partner institution], contacted colleagues who worked on studies they did and collaborated with them for different meetings and projects. Those are practical outputs that are very relevant for my work now and highly valuable for what I do.”

Another example of the reach of the program’s overseas professional network was a project collaboration between a GGF alumna and Foresight Intelligence, our GGF foresight expert’s consulting firm. This partnership eventually even led her to join the company’s team. Today, she is the Indonesia lead for Foresight Intelligence. As one fellow pointed out that, “these opportunities, after the program, make it meaningful in the long-term.”

GGF 2030 fellows enjoying a well-deserved break after a long working day.

Conclusion

The GGF approach to multilateral and cross-cultural dialogue allowed us to create and hold a safe space in which our participants could come together, engage with each other in a meaningful way, really “see” one another, and – most of all – engage all their senses to explore and grasp different political realities and lived experiences. The most difficult and the most meaningful discussions between fellows from different backgrounds unfolded when they were open, honest and, knowingly or not, empathetic toward one another. Sometimes, these conversations happened organically on the sidelines. Sometimes, participants agreed to disagree while still exercising compassion and acknowledging where the ‘other side’ was coming from. As Andrew Linklater observed: Compassion “is a universal property of all social systems. All societies can recognize compassionate traits in others; that is one reason for their mutual intelligibility and one explanation of why they are capable, in principle at least, of expanding the scope of moral concern to include outsiders.”

The GPPi team consciously crafted a collaborative environment that allowed the different generations of GGF fellows to learn from each other, learn about themselves and challenge their own as well as other fellows’ biases. Methodologically, the program’s unique combination of scenario planning and generative facilitation engaged our fellows in intellectual acrobatics, encouraged their active participation, built trust, nurtured collaboration in pursuit of a common goal, and – where possible – helped them reach consensus on how to best address complex global challenges. Our methodology tapped into the groups’ collective intelligence and thus turned differences into advantages by allowing the participants to combine their strengths. It also set the frame for them to arrive at higher-order ideas and solutions that leverage the wisdom that resides not just in any one fellow but in the whole group. To quote Ken Cloke: “Dialogue is not just a simple back and forth between two monologues, but the principled way that new, creative, holistic ideas emerge. It is therefore not only useful in social problem-solving, but the basis for political collaboration and a new and higher form of human intelligence.”

One thing is clear: in our highly connected and interdependent world, individual countries that retreat into isolation and wish away the threats that face all of us as a global community do so to their own detriment. What is more, they ignore the opportunities that arise from multilateral cooperation. Challenges that transcend boundaries require new ways of working together globally. Especially in times of rising geopolitical tensions, we need to build the personal connections that allow committed individuals to pursue cooperation across divides. The GGF multilateral dialogues program and our unique approach contributed to this effort. We hope this experience can inspire future efforts.

Joel Sandhu is the program coordinator of the Global Governance Futures program. He is a certified generative facilitator and project manager at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi), where he leads the institute’s work on cross-cultural and cross-sectoral dialogues with a focus on global governance issues.

This first appeared on GGF's website.

* While carrying out interviews with GGF alumni that informed this article, I benefitted greatly from the support of Coco Aglibut. My sincere thanks.

- The first two rounds of the Global Governance Futures (GGF) program (GGF 2020 and GGF 2022) were supported by the Robert Bosch Foundation with seed funding from the Transatlantic Program of the German Federal Government. The Foundation then generously supported the remaining four rounds of the program (GGF 2025, GGF 2027, GGF 2030, and GGF 2035). The program was eventually renamed the Global Governance Futures – Robert Bosch Foundation Multilateral Dialogues program (or GGF).

- Tetlock, Philip E, Expert Political Judgement: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, Princeton University Press, 2017, p. 190.

- The GGF program published a total of 18 scenario reports on a wide range of global governance policy issues. The range of GGF products also includes opinion pieces, online interviews, studies and podcasts. All of these are accessible to the public: https://www.ggfutures.net/analysis

- The network of GGF partners consisted of leading academic institutions, foundations and think tanks from Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Africa, and the United States. They include the Hertie School of Governance, Fundação Getulio Vargas, Tsinghua University, Fudan University, Institut français des relations internationales, Ashoka University, Center for Policy Research, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research, Keio University, South African Institute of International Affairs, Brookings Institution, and Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.

- Scharmer, C. Otto, Theory U, Leading from the future as it emerges, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2016, p. 344.

- Weisbord, Marvin and Sandra Janoff, Future Search, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2010, p. 205.

- Ibid.

- Cohen, Raymond, Negotiating Across Cultures, United States Institute of Peace Press, 2007.

- Scharmer, C. Otto and Katrin Kaufer. Leading From the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2013, p.12.

- The 2020/21 round showed us that there is no replacing actual, physical interaction. That said, the Coronavirus pandemic has taught us that multilateral policy dialogues can be facilitated through online interactions where some essence of dialoguing can be transmitted into the digital sphere, as the GGF 2035 fellows can attest. However, in-person interaction and the overall quality of the experience that it brings is irreplaceable. On multiple occasions, we had to weigh this against the constraints of the global pandemic and climate change. The GGF program offset participants’ carbon emissions related to carrying out and attending the program.

- This observation is based on post-GGF survey evaluations that we conducted after every meeting over the course of 10 years. The surveys indicated that the vast majority of all GGF alumni felt that their intellectual horizons were expanded as a results of open and candid exchanges on policy, cultural and societal issues. The GGF program was a safe space for them to open up and feel like they can respectfully challenge preconceived notions and biases in the room.