Post-Mugabe Zimbabwe Retreats from Western Outreach, Embraces Africa

Brooks Marmon explores the propaganda struggles and diplomatic debates emanating from Western sanctions on Zimbabwe.

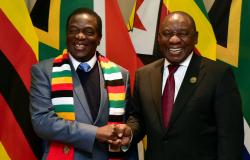

Africa fully supports the post-Mugabe regime of President Emmerson Mnanagagwa and wants Western sanctions on Zimbabwe scrapped. This was the message of an October 25th anti-sanctions day campaign carried out throughout the 16-member Southern African Development Community (SADC) and also backed by the Africa Union (AU).

Africa’s marked backing for Mnangagwa’s predecessor, Robert Mugabe, had long been evident. Despite repressive and internationally controversial policies, Mugabe’s strong anti-western rhetoric helped Zimbabwe secure Chairmanships of both SADC and the AU in the later years of his rule. Although Mnangagwa had served under Mugabe since independence in 1980, he replaced his mentor via an armed intervention in November 2017. This manoeuvre initially caused some unease across Africa, particularly outside of the SADC region.

The AU has recently signalled more aggressive moves to promote democracy, such as temporarily suspending Sudan to ensure a civilian transition. However, just as many African member states of the ICC refused to recognise an arrest warrant for former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, perceptions of ongoing Western pressure on Zimbabwe appear to be driving solidarity with Mnangagwa. This strong backing in the face of Western censure provides a template for African autocrats to deflect democratic pressures in continental and regional bodies.

The SADC initiative was resolved at a summit meeting in August as an act of solidarity in response to a long-standing EU and US sanctions regime against Zimbabwe. Imposed during the country’s post-2000 fast track land reform process, the EU subsequently rescinded most of its measures in 2013. However, the US updated the Zimbabwe Democracy and Economic Recovery Act (ZIDERA, 2001) which calls for “democratic change” in Zimbabwe just last year. According to the US Ambassador to Zimbabwe, ZIDERA targets 141 individuals or firms linked to ZANU-PF, President Mnangagwa among them.

Since their inception, sanctions have been something of an own goal for the West. ZANU-PF remains firmly entrenched in power and regularly draws on ZIDERA as a convenient scapegoat for the country’s massive economic problems. After recently abruptly dropping the US dollar as a legal currency, Zimbabwe’s inflation is now the highest in the world. ZANU-PF also points to sanctions as a sign of the West’s pursuit of regime change and desire to restore land to dispossessed white farmers.

However, the 25 October activities mark the most significant and internationalised example of ZANU-PF attempts to undermine sanctions. The day was declared a public holiday and protest marches and rallies were held across Zimbabwe. Supporters were bused into the national stadium in Harare and provided with entertainment and snacks. Clad in a matching white t-shirt and baseball cap emblazoned, ‘SADC United Against Sanctions,’ Mnanagagwa delivered a 30-minute address before thousands. He reprised the ZANU-PF motif, widely accepted in Africa, that “sanctions were a reaction to the just and necessary act of redistributing our land.”

While the denunciation of sanctions has formed a cornerstone of ZANU-PF propaganda for nearly two decades, the activities surrounding the anti-sanctions day event on 25 October signal the consolidation of a political shift.

After Mnangagwa came to power two years ago, a concerted campaign was launched to reset ties with the West. In 2018, Zimbabwe applied to rejoin The Commonwealth, which it withdrew from in 2003. Mnangagwa, formerly a leading figure in a Marxist liberation movement, penned an op-ed in the Financial Times in which he styled himself a neoliberal reformist in the same vein as Margaret Thatcher. An indigenisation policy which hindered foreign investment was repealed and promises of compensation were made to evicted white farmers. Western organisations were invited to observe the 2018 general elections for the first time in years. Zimbabwe appeared at risk of losing the pan-African lustre that Mugabe’s militancy had garnered.

This re-engagement trajectory was abruptly derailed when security forces killed several protestors just ahead of the release of election results. Lethal violence flared again at the beginning of this year. For a weakened administration, the strong show of solidarity from SADC and the AU on 25 October was significant. Widespread regional support has been a core pillar of ZANU-PF’s longevity. Africa’s renewed push to end Western sanctions on Zimbabwe signals that while Mnangagwa lacks Mugabe’s pan-African pedigree, he now enjoys the continent’s backing.

Critically, the anti-sanctions day commemorations also heralded a rapid decay in Zimbabwe’s bi-lateral relations with the US, the principal object of the 25 October lobbying. Fallout from the anti-sanctions initiative indicates that Zimbabwe’s re-engagement with the West, which progressively deteriorated amidst a number of missteps by Mnangagwa, is now firmly in abeyance.

US officials launched an assertive counter-offensive against the anti-sanctions events taking place across southern Africa, but primarily centred around Zimbabwe and South Africa. On 24 October, Jim Risch, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair released a taunting pro-sanctions statement condemning ZANU-PF’s “bad governance” alongside SADC’s support for a “kleptocratic regime.” The same day, the US Ambassador to Zimbabwe, Brian Nichols, penned an op-ed in a Harare paper, News Day, under the title, “It’s Not Sanctions, It’s Corruption, Lack of Reforms.” Following Risch’s example, Nichols pulled no punches, declaring that the country’s economic woes were the result of “corruption, economic mismanagement, and failure to respect human rights and uphold the rule of law.”

The frenetic American counter-assault continued on social media the following day where the US Embassy’s Twitter account unleashed a barrage of tweets pointing to state corruption in Zimbabwe under the hashtag #ItsNotSanctions. Among a range of criticism, tweets drew attention to Zimbabwe’s poor performance on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (160 of 175) and the misappropriation of funds for a Command Agriculture program, a cherished Mnangagwa initiative. In Washington, the State Department announced that Owen Ncube, Minister of State for National Security would be barred from entering the US due to his “gross violations of human rights.”

In the Donald Trump era of cultivated social media-based confrontation, the rapid escalation in tensions between the US and Zimbabwe over the space of 48 hours potentially signals a wider new direction in an age of virtual diplomacy. Countries like Zimbabwe, facing no threat from terror groups and suffering under a marginal and diminishing economy, may face emboldened responses from Western diplomats when they attempt to assert themselves. Whereas in a previous era the US Embassy may have simply released a lone, carefully worded statement on the anti-sanctions campaign, Twitter allowed it to produce a running critical commentary and further stoke tensions.

While the State Department effectively signalled its willingness to aggressively respond to Zimbabwean (and SADC) criticism and attendance at Mnangagwa’s Harare rally was sparser than anticipated, ZANU-PF probably emerged best off following the face-off of 25 October.

Glaringly, neither Senator Risch’s statement nor Ambassador Nichols’ op-ed attempted to highlight any positive achievements of the sanctions program, or explain why it was particularly necessary for Zimbabwe, given the global prevalence of corruption and autocratic regimes. Risch’s broader regional criticism, in the aftermath of strong condemnation from Botswana, home to SADC, over President Trump’s shi*hole comment may also signal an ongoing slide in relations with the subregion. Only in September, after a gap of nearly three years, did the US appoint an Ambassador to South Africa, Zimbabwe’s most important ally.

The US missed an opportunity to address ZANU-PF’s framing of the sanctions debate by deflecting to issues of corruption and accountability. Zimbabweans on Twitter and readers of News Day are likely well aware of the extent of government graft. However, they have smarted over ZIDERA’s symbolic injuriousness and its hard to quantify tangible repercussions. A professor at the University of Zimbabwe claimed that sanctions have cost the enfeebled economy over $7 billion. Mnangagwa’s statement that sanctions “are neither ‘smart’ nor ‘targeted’” was probably received with some degree of resonance.

More importantly, Mnangagwa has shown that post-Mugabe ZANU-PF maintains the endorsement of the sub-region and the continent. This backing was key to Mugabe’s stranglehold on power amidst historic rates of inflation and a defeat in the first round of the 2008 election. With this firm show of support, it appears that any reform in Zimbabwe will only take place on ZANU-PF’s terms.

Brooks Marmon is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, researching pan-African influences on Zimbabwean politics. Follow him @AfricaInDC.

Image: GovernmentZA via Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)