This year marks the 15th anniversary of the “BRICs,” the term I coined to refer to the major emerging economies: Brazil, Russia, India, and China (South Africa was added in 2010). Recently, my brief tenure in the British government came to an end, following the completion of an independent review on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) that I had been chairing. As I ponder what to do next, I can’t help but return to the subject of the anniversary. Have those large and promising emerging economies fulfilled expectations?

Perhaps the simplest way to answer this question relates to my work on the AMR review, which was launched by former British Prime Minister David Cameron in 2014. On September 21, we achieved a major victory: a high-level agreement by the United Nations on the topic.

After the agreement was reached, a German television crew that had occasionally followed my team and me as we worked to spread awareness of AMR asked me, on air, whether the outcome was more important than the BRIC concept. Without even waiting for me to answer, they declared that it obviously was. And they were right: no economy, emerging or otherwise, can hope to be successful if it is plagued by a health threat as serious and uncontrollable as AMR.

But there is more to the story: the BRICS are just as important to tackling AMR as tackling AMR is to the BRICS. South Africa, for one, was a key supporter of the United Kingdom in discussions about AMR at the recent G20 summit in Hangzhou, China, and the issue might not have ended up in the meeting’s communiqué without its support.

And that is the point. The BRICS today, like in 2001, have a vital role to play in tackling the most pressing international challenges. In fact, I came up with the acronym not just because the letters fit together, but also because of the word’s actual meaning: these emerging economies, I argued in my 2001 paper, should be the building blocks of freshly overhauled global financial and governance systems.

Yet, as we approach this year’s autumn meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, the BRICS remain severely underrepresented by these critical institutions. If this does not change, with reforms going much further than they have so far, we will soon find that “global governance” is no longer global at all.

To be sure, the BRICS have lately been going through a rough time. The economic performance of Brazil and Russia, in particular, has been very disappointing so far this decade, to the point that many now perceive those countries as unworthy of the status the acronym afforded them.

But the suggestion that the BRICS’ importance was overstated is simply naïve. The size of the original four BRICs economies, taken together, is roughly consistent with the projections I made all those years ago.

Both Russia and Brazil now account for a similar share of global GDP as they did in 2001, though Russia, according to my simple calculation, might currently be outside the world’s ten largest economies. Brazil, for all of its considerable problems, is higher in the world ranking today than even I had envisaged back then.

India continues along roughly the same path it was on 15 years ago. With the right structural reforms, it may even be able to achieve a sustained period of Chinese-style double-digit economic growth.

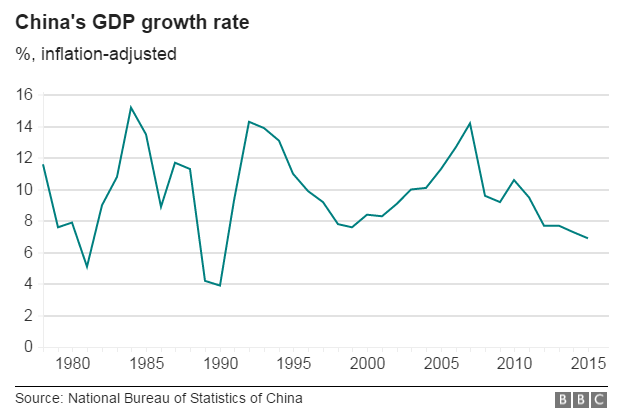

But the biggest BRICS success story remains China, which, despite its recent slowdown, has far exceeded expectations. If the economy grows at an annual rate of around 6% for the remainder of the decade, it will fulfill my 20-year projection.

This is not to diminish the challenges confronting China. But if it manages to address the most urgent among them – downside deflationary risks – its much-discussed debt challenge will become far more manageable.

Fortunately for China, other countries want – or should want – it to succeed. After all, a dynamic Chinese economy is in the interest of many other countries, especially those that can export the goods and services that a more modern, consumer-driven China needs. In fact, the rise of the Chinese consumermay well be the most important single global economic variable today – even more important than, say, the economic problems afflicting Europe and Japan or questions about India’s enduring global relevance.

The potential barriers to the BRICS’ growth and development are many, including health threats like AMR, educational challenges, inadequate representation in global governance bodies, and a number of short-term cyclical problems. Policymakers worldwide must commit themselves to dismantling these barriers, and enabling the BRICS to fulfill, finally, their true potential.